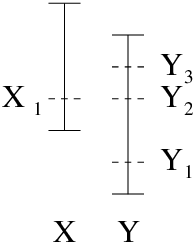

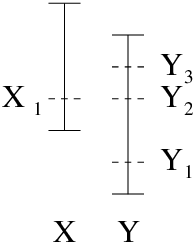

| Figure 9.2: Comparing two bounded reals |

When working with bounded reals, some of the usual rules of arithmetic no longer hold. In particular, it is not always possible to determine whether one bounded real is larger, smaller, or the same as another. This is because, if the intervals overlap, it is not possible to know the relationship between the true values.

An example of this can be seen in Figure 9.2. If the true value of X is X1, then depending upon whether the true value of Y is (say) Y1, Y2 or Y3, we have X > Y, X =:= Y or X < Y, respectively.

Figure 9.2: Comparing two bounded reals

Different classes of predicate deal with the undecidable cases in different ways:

?- X = 0.2__0.3, Y = 0.0__0.1, X > Y.

X = 0.2__0.3

Y = 0.0__0.1

Yes

?- X = 0.2__0.3, Y = 0.0__0.1, X < Y.

No

?- X = 0.0__0.1, Y = 0.0__0.1, X < Y.

X = 0.0__0.1

Y = 0.0__0.1

Delayed goals:

0.0__0.1 < 0.0__0.1

Yes

?- X = Y, X = 0.0__0.1, X < Y.

No

?- X = 0.2__0.3, Y = 0.0__0.1, X == Y. No ?- X = 0.0__0.1, Y = 0.0__0.1, X == Y. X = 0.0__0.1 Y = 0.0__0.1 Yes ?- X = 0.2__0.3, Y = 0.0__0.1, compare(R, X, Y). R = > X = 0.2__0.3 Y = 0.0__0.1 Yes ?- X = 0.1__3.0, Y = 0.2__0.3, compare(R, X, Y). R = < X = 0.1__3.0 Y = 0.2__0.3 Yes ?- X = 0.0__0.1, Y = 0.0__0.1, compare(R, X, Y). R = = X = 0.0__0.1 Y = 0.0__0.1 Yes ?- sort([-5.0, 1.0__1.0], Sorted). Sorted = [1.0__1.0, -5.0] % 1.0__1.0 > -5.0, but 1.0__1.0 @< -5.0 Yes

Note that the potential undecidability of arithmetic comparisons has implications when writing general code. For example, a common thing to do is test the value of a number, with different code being executed depending on whether or not it is above a certain threshold; e.g.

|

When writing code such as the above, if X could be a bounded real, one ought to decide what should happen if X’s bounds span the threshold value. In the above example, if X = -0.1__0.1 then a delayed goal -0.1__0.1 >= 0 will be left behind and Code A executed. If one does not want the delayed goal, one can instead write:

|

The use of not ensures that any actions performed during the test (in particular the set up of any delayed goals) are backtracked, regardless of the outcome of the test.

Finally, if one wishes Code B to be executed instead of Code A in the case of an overlap, one can reverse the sense of the test:

|